AN ALASKAN DINER MYSTERY

CHAPTER 1

I DISCONNECTED THE PHONE CALL, WAITING FOR THE sirens, ready to be arrested and thrown into the women’s side of the tiny jail in Elkview, Alaska. A fine way to settle back in my hometown after a few years away.

I had just lied to my mother. Worse, I’d done it while looking into her eyes on FaceTime. Trusting, beautiful brown eyes that almost perfectly matched her hair. My hair, too. How had that falsehood rolled off my tongue?

The last time I’d lied to Evelyn Cooke, I was six years old and I’d blamed cousin Petey for starting the fight in his backyard. And that was technically not a lie, because we’d shoved each other into his sandbox at the same time.

But this afternoon, at thirty-three years old, I’d told a whopper. Was it because I was distracted by warnings of the freezing rain heading our way, icy rain that would keep tourists away from the Bear Claw Diner? My diner, as of almost a year ago, when Mom decided to retire and travel with Dad, who was still giving management workshops all over the world. To think how thrilled I’d been that Mom would entrust everything to me—the diner, the staff, her recipes, her great following of regular patrons, and even Eggs Benedict, aka Benny, her beautiful orange tabby.

“How is everything going, Charlie?” Mom had asked from the deck of a cruise ship headed down the Danube. Or was it up the Danube? I hadn’t had much time for travel myself, what with a brief, ill-advised stint as a law school student in nearby Anchorage, followed by culinary school down in San Francisco, three thousand miles and one time zone away. And now I had full responsibility for a twenty-four-hour diner.

“Is Oliver okay with the new recipe you suggested?” Mom asked, catching me off guard.

“Absolutely,” I’d answered, passing over the knock- down-drag-out in the kitchen right after lunch. “He loved the idea.”

In truth, an imbroglio had begun when I proposed a simple change to our signature bear claw recipe. My position was that adding a bit of chocolate to anything was an improvement, but I should have known better than to suggest a change to my head chef.

Oliver Whitestone, whose fiftieth birthday bash I’d just missed last year, had been with Mom since the early days of the Bear Claw and had always resisted any variation in the menu. Who was I, too green in his eyes to even be called a rookie, to mess with success? I was a mere child, in middle school, when he was hired at the Bear Claw. Never mind that I’d grown up there, doing my homework after school, twisting on a red vinyl stool, trying to see my reflection in the bright chrome trim, sometimes pushing the limit of the legal age for waitressing or kitchen work. And never mind that I’d been to culinary school, though admittedly not in Paris, where Oliver was trained.

Oliver liked to remind us that he could be cooking anywhere in the world, emphasizing his point by spreading his sadly short arms to encompass Europe, I guessed.

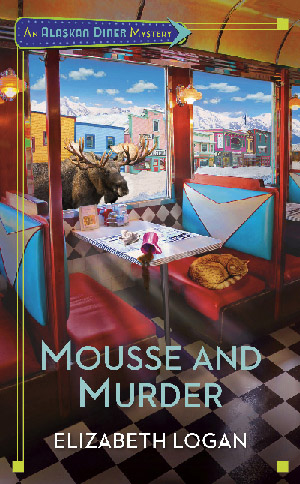

“But you chose us,” I’d say, and spread my own much longer arms to take in our retro black-and-white tile with seating for fifty, as long as a few of the customers were skinny. I wasn’t always sure Oliver understood my sarcastic tone. Just as well.

Today I’d inadvertently escalated the rift between us. I’d brought in a chocolate bear claw recipe to show the staff and suggested they give it a try over the next few days. An innocent experiment. Oliver had taken the paper from my hands and torn it into tiny pieces.

I wasn’t proud of the shouting match that followed, within easy earshot of the remaining lunch crowd. The rest of the kitchen staff, used to these sparring contests, carried on with their work. The disruption lasted several minutes and ended, as usual, with Oliver storming out of the kitchen and slamming through the back door. He’d tossed his white jacket and hat over the chopping table, grabbed his parka from a hook, and muttered something about any new recipe in connection with his dead body.

It wasn’t the first time he’d left in a huff, though not always because of me. He’d once disappeared for an hour during a rush because one of his helpers showed up eating a cheeseburger from Chief Beef, a new fast-food place in town.

Who knew where Oliver was now? Probably with his new girlfriend, a construction worker on the old drive-in movie renovation project down the road.

I walked around the empty diner, refilling the ketchup, mustard, salt, and pepper containers, with my eyes on the door, ready to welcome Oliver back and issue an apology if needed. A temporary truce would be better than nothing. It wasn’t as if I needed chocolate bear claws tomorrow, or at all, if it came down to that.

I’d known it would be tricky working with Oliver, who’d been used to one boss for many years. If my mom could even be called the boss, she was so mellow. Besides being on opposite ends of the spectrum height-wise — I towered over her from when I turned thirteen — Mom and I were also very different in terms of temperament.

I found part of a meatloaf sandwich behind the fake jukebox and smiled as I remembered the little boy who’d sat there earlier, probably annoyed that the only real jukebox was the large electronically operated console at the back of the diner. Oliver didn’t mind upgrades that weren’t edible.

Fortunately, it was already after three o’clock in Elkview, and the Danube was ten hours later. Mom had probably been too tired to catch the lie I was sure was written all over my face. The fact that she’d said simply, “Good,” and then “Love from Dad, too. Talk tomorrow,” meant I was home free. For now. Phew. Both a good “phew,” because I didn’t have to worry my mom with a tantrum story that was all too familiar to her — Oliver had been her second-in-command for as long as I could remember — and a bad “phew,” because I’d have a hard time sleeping knowing I’d kept the truth from her. I’d done it so it wouldn’t ruin her trip, I told myself.

So you wouldn’t look like you couldn’t handle your new responsibilities was hard to own up to.

I continued my hit- and-miss cleanup — filling the metal napkin holders in each booth and along the counter, adding environmentally safe straws and clean place mats as needed, still trying to justify my lie, which I’d managed to reduce from “black” to “little white.” I finally realized it might be more productive if I talked to someone other than myself. In a happy coincidence, my childhood friend Annie Jensen had also moved back to Elkview, to manage her family’s inn down the road from the Bear Claw. Even happier, we had promised each other at least two movie dates a month as soon as the drive-in reopened, no matter the state of our respective businesses. I called up Annie’s number and got voicemail.

Too bad. But a useful offshoot of the failed attempt to contact Annie came to me. Thanks to the orderly arrangement of my contacts list, I had a stabbing reminder of a meaningful action I needed to take, one long overdue. JENSEN was immediately after JAMISON on my screen. I gritted my teeth and highlighted Ryan Jamison, my ex-fiancé, and one of the reasons I’d fled from San Francisco. Ryan, the SF Bay Area lawyer who saw greener pastures with one of his paralegals and neglected to inform me in a timely fashion. I hit Delete and felt a shiver of glee, as if I’d punched him in the gut, but without the assault charge.

I knew my next option for companionship would be no-fail, even if remote. It was love at first sight for Benny and me. Sure, it might have been because I’d arrived in his life armed with an automatic feeder programmed to dispense his favorite food throughout the day whether or not I was home. There was nothing wrong with a little bribery — motivation?—to win over a beautiful orange and white tabby. Benny, renamed by Mom, was a reluctant castoff from a friend of hers who had moved overseas. I wondered which country didn’t accept American cats.

“Kind of defeats the purpose,” Mom had said when she saw Benny’s feeder. “I gave you Benny so you wouldn’t stay at the Bear Claw twenty-four-seven. Now you’re telling me you’re going to feed and pet him through your phone?” She shook her head.

I’d dissuaded her of the remote petting idea, though I thought it couldn’t be far off, given how quickly technology changed these days.

It wasn’t only Mom who thought I went over the top when I added a camera to the system, one that included two-way audio. How many ways can a cat say meow? A lot, it turns out, depending on his mood. I had come a long way, mastering Benny’s meows, trills, purrs, and the occasional growl when he was unhappy.

A selection of games that pets could play were all accessible from the app on my smartphone. I called the unit “the Bennycam.” So far, I’d tested the laser game only once and was still a little wary of hurting Benny if the beam he was supposed to be chasing around the floor went astray and chased him back.

Today I tuned in and waited a few minutes for Benny to get within camera range. I’d set the camera up in the open space between my kitchen and dining room, giving me video access to the area where Benny spent the most time when he was awake. The app had already given me the feedback that he’d consumed three ounces of food since I saw him last. I’d made a quick visit home to Benny right after my blowout with Oliver, ostensibly to pet my cat, but more for my own benefit, for him to comfort me.

When Benny pawed his way to the camera, I gave myself a virtual pat on the back for being in sync with my pet and watched as he checked out the feeder tray and nibbled. I allowed him a semiprivate moment for noshing, then started in on my roster of concerns, starting with, “What am I going to do if Oliver doesn’t come back in an hour to prep for the dinner shift?” Although Benny might not have been aware of it, he answered with, “Call Victor and lure him in as a substitute, with a promise of time and a half.” As usual, “Now leave me alone while I nap” was implied by his tone.

I could promise Victor a less-than-full crowd this evening. It was Monday, typically slow to begin with, but with the added deterrent of constant weather warnings on radio and television. We’d probably be feeding only the poor tourists who were unaware that winter could still be raging through March in Elkview.

Travelers from all over the world came here to walk amid ice glaciers and snow-covered mountains along the scenic Glenn Highway. We Alaska natives always found it amusing that many of them would act surprised or even complain about the cold weather. The word was that the clothing store on Main Street did a thriving business from tourists who had an immediate need for a heavy sweater or jacket, and woolen caps flew off the shelf.

I left Benny napping in a cone of sunshine on the living room floor and got back to my diner issue. I texted and emailed the delinquent Oliver, plus the few friends of his that I knew, and then, giving up, texted Victor. As a backup to the backup, I headed for the freezer myself and pulled out a large tray of our original- recipe individual shepherd’s pies, along with another tray filled with corn muffins.

When the small bells over the front door tinkled a few minutes later, I held out hope for Oliver, but a glance through the serving window showed Elkview’s finest, Alaska State Trooper Cody Graham. The law man, simply “Trooper” to those who knew him well, headed for his favorite booth at the rear of the train-car-shaped diner. So he could sit against the wall, facing everyone, his back to no one? Not that he would admit it. I smiled, thinking about how I’d pictured him here earlier, arresting me for fibbing in the first degree.

“Are those shepherd’s pies I smell?” he asked.

“You can’t possibly smell them, Trooper. They’re still frozen solid.”

“Did you put out a call for your MIA chef?”

I was chuckling now. “Yes. How did you know?”

“Then you’re on kitchen duty until you can bring in reinforcements.”

“Right.”

“Then those are shepherd’s pies I smell.”

“I’ll get one started,” I said.